How Andor Got its Backstory from a Tabletop RPG

In 1987, 'Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game' added vital details to the sci-fi universe that are still used today in movies, games, novels, and streaming series

The streaming series Andor (which returns to Disney+ for a second season on April 22) was met with great acclaim when it premiered in 2022, and not just from faithful Star Wars fans. Critics raved about the depth and sophistication of the show.

What set the series apart from the other entries in the sci-fi franchise? Instead of focusing on the dastardly planet-destroying machinations of a monolithically evil Sith lord like typical Star Wars fare, Andor aimed a little further down the food chain: at midlevel officials within the Imperial Security Bureau. This focus on the quotidian activities of dour apparatchiks infighting and jockeying for position within a vast bureaucracy made the show feel more like a LeCarre novel than a Lucasfilm production. Andor offered similarly rich insights into how a decentralized and clandestine network like the Rebel Alliance went about gathering intelligence, recruiting operatives, and deploying them in field operations.

Critics and fans marveled at how the show’s fleshed-out universe helped to make that galaxy far, far away feel so much more lived-in and real. But Andor didn’t make up that backstory out of whole cloth—35 years before, Star Wars: The Role Playing Game was the first piece of media to describe the inner workings of those organizations in exhaustive detail. The Imperial Security Bureau wasn’t dreamed up by George Lucas—it was invented by a game designer.

The designers of that game had to fill in that backstory—players would need all of those granular specifics to help them craft their Dungeons & Dragons-style tabletop roleplaying experiences. This means that a handful of role-playing game designers added as many minutiae, tropes, and story elements to the Star Wars universe as anyone before or since, including George Lucas himself.

Star Wars: The Role Playing Game isn’t well-known today, but many of the characters, creatures, vehicles, and institutions that those tabletop dice geeks dreamed up were fully incorporated into the ongoing and ever-expanding canon of Star Wars. It might have even helped to bring the franchise back from the dead…

A long, long time ago—in 1986

Imagine living in a time when it seemed like the Star Wars phenomenon had run its course. It’s almost impossible to conceive of now. Even in the Nineties, before the prequels had been announced, or during that terrible drought between the prequels and The Force Awakens, there were still endless tie-in TV shows and comics and action figures and video games and Darth Tater Potato Heads, all helping to keep the franchise alive.

But there was a period of time when the Star Wars phenomenon was completely moribund. In the late Eighties, the original film trilogy was a distant memory, the kid-friendly TV specials were done, the Saturday morning cartoons had run their course, and there were no new novels or toys on the horizon.

Most people quite naturally assumed that Star Wars was never coming back, because that was generally how things worked back then. This was an era before every single intellectual property that had ever been vaguely popular, from Ghostbusters to Gremlins to The Karate Kid to Magnum P.I., got rebooted and recycled. At the end of the Reagan era, it genuinely seemed to many that the lifecycle of George Lucas’ film franchise had petered out.

That’s why it was sort of crazy that West End Games, a maker of tabletop role-playing games, was willing to spend what seemed at the time like a fortune to license Star Wars. Bill Slavicsek, who helped create Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game for West End, remembers telling a friend who worked for Marvel Comics about the project. “He said, ‘Why would you make that?! That’s a dead license!’” he recalls.

But Star Wars wasn’t dead. And the tabletop game was one of the things that helped keep the franchise's flame alive for countless fans. West End’s RPG wasn’t merely a stopgap. In giving players the robust framework they needed to have their own adventures in Star Wars, the game became a cornerstone of the Expanded Universe of spinoff books and games and comics and merchandise that followed.

Tabletop games are sort of amazing. With a handful of dice, a couple of rule books, some graph paper for mapping environments, and a few willing friends, players could create their own limitless world—a sort of shared hallucination. “It’s an act of group storytelling,” says Slavicsek.

It was also a crowded and highly competitive industry by the mid-1980s. Dungeons & Dragons creator TSR was the major player, but upstart companies were rushing to create competing games built around different settings and licenses. Before making a bid for Star Wars, West End had success with original RPGs like the dystopian sci-fi comedy Paranoia, and an adaptation of Ghostbusters.

Greg Costikyan, a co-creator of Paranoia, was one of the people tasked with securing the Star Wars license. “We flew out to California to meet with Lucasfilm,” he says. “We made a bid of $100k. We later learned that TSR had tried to get the license too, but they only bid $70k.” (I’m sure it seemed like a gamble at the time, but think about that for a minute—they scored the rights to make a game based on all of Star Wars and its associated intellectual property, free and clear, for the equivalent of less than an inflation-adjusted quarter of a million dollars.)

Costikyan says that the people at Lucasfilm didn’t seem to think that the franchise was dead at that point — Lucas’ original vision had called for nine films, after all. But they were fully aware that Star Wars was essentially in hibernation—as if frozen in carbonite. “Lucasfilm thought that an RPG could help keep Star Wars active in the minds of geeks, which was why the licensing deal had some value to them,” says Costikyan.

Costikyan set to work on creating the rulebook for Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game. His design of it would be a crowning achievement for some people, but it was a just sidenote for him. He would go on to create influential and innovative tabletop, PC, mobile, and social games in a variety of genres, and write extensively on game design. He won a Game Developers Choice Maverick Award for his tireless early efforts to create digital distribution systems for indie video games.

Costikyan had been interested in the franchise since he first encountered it at World Sci-Fi Con the year before the first film was released. “The filmmakers had taken a room at the con, and were showing stills and little clips,” he says. “It looked like it had the makings of a really good space opera.”

He saw the original film at an early matinee after an all-night D&D session. A fellow participant in that role-playing marathon had bought a ticket to Star Wars, but was too exhausted to attend. Costikyan bought the ticket and watched the film, then stuck around to watch the next showing.

“There’s great worldbuilding in that film, often done with very simple special effects,” he says. “Like the two suns in the sky on Tatooine. That’s just a double exposure, but I’d never seen anything like that. I also liked the fact that the characters weren’t all nice and happy. There was an interesting dynamic where they got upset with each other, they bantered and whined. It’s so much more compelling than just being all nice and cool and happy with each other.”

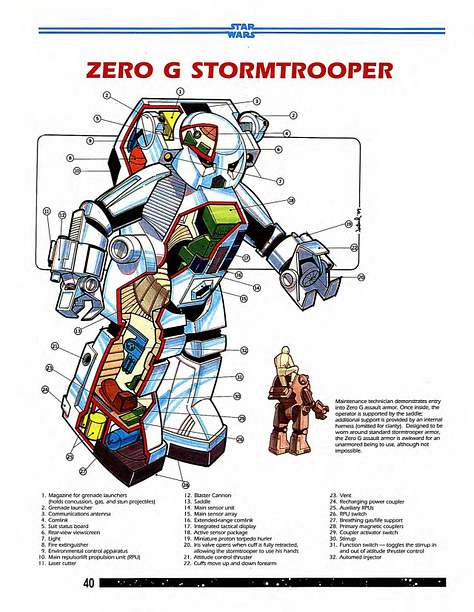

Now that he was working on the game, he rewatched the films intensively. West End wouldn’t just have to recreate the set pieces from the film — they would actually have to systematize how the action played out in that universe. “Like, exactly how fast would your body temperature drop on the ice planet of Hoth?,” says Costikyan. “There needed to be mechanical implications for what we saw onscreen. In the films, Stormtroopers famously cannot hit anything. In the game, we needed to allow them to hit things occasionally; otherwise, there’s no drama involved.”

“I had a couple of design objectives,” says Costikyan. “Unlike most RPGs, I knew that we weren’t selling purely to people who were already into D&D. This needed a simpler paradigm.”

He focused on the most intense and memorable moments in the films: Think of the hapless droids trying to traverse a corridor in the middle of a pitched battle, pursuing their own secret agenda while laser blasts ricocheted around them. Think of Luke and Leia preparing to swing across a chasm on a flimsy rope, sharing a quick kiss for luck (a plot detail that seems far more icky with the benefit of hindsight.) “I wanted a system that really lends itself to those sorts of moments, those exploits that were cinematic and exciting,” says Costikyan. He also instructed game masters on how to coax players into bantering and bickering like the original film protagonists did.

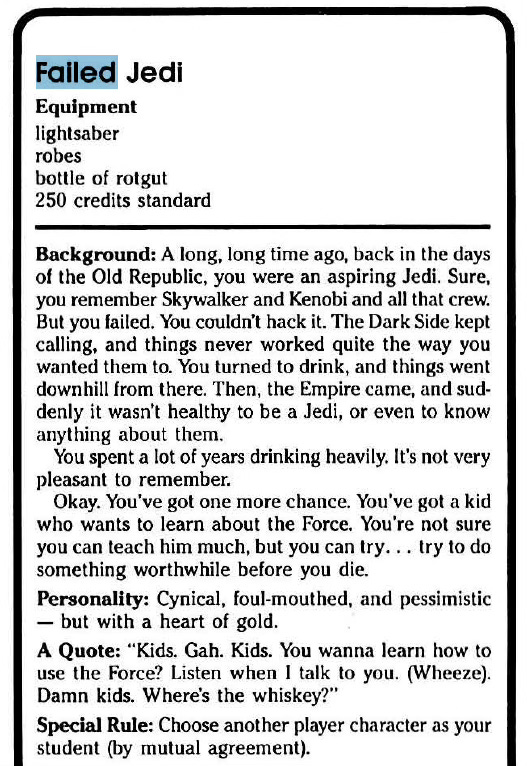

West End’s designers divided up the different types of characters in the film into different classes that players could choose to be. They also introduced several archetypes that hadn’t appeared in the film. “There were obvious ones like bounty hunters and smugglers,” says Costikyan. “A particular favorite of mine was the failed Jedi — a drunk who didn’t quite make it, but had some control of the Force.”

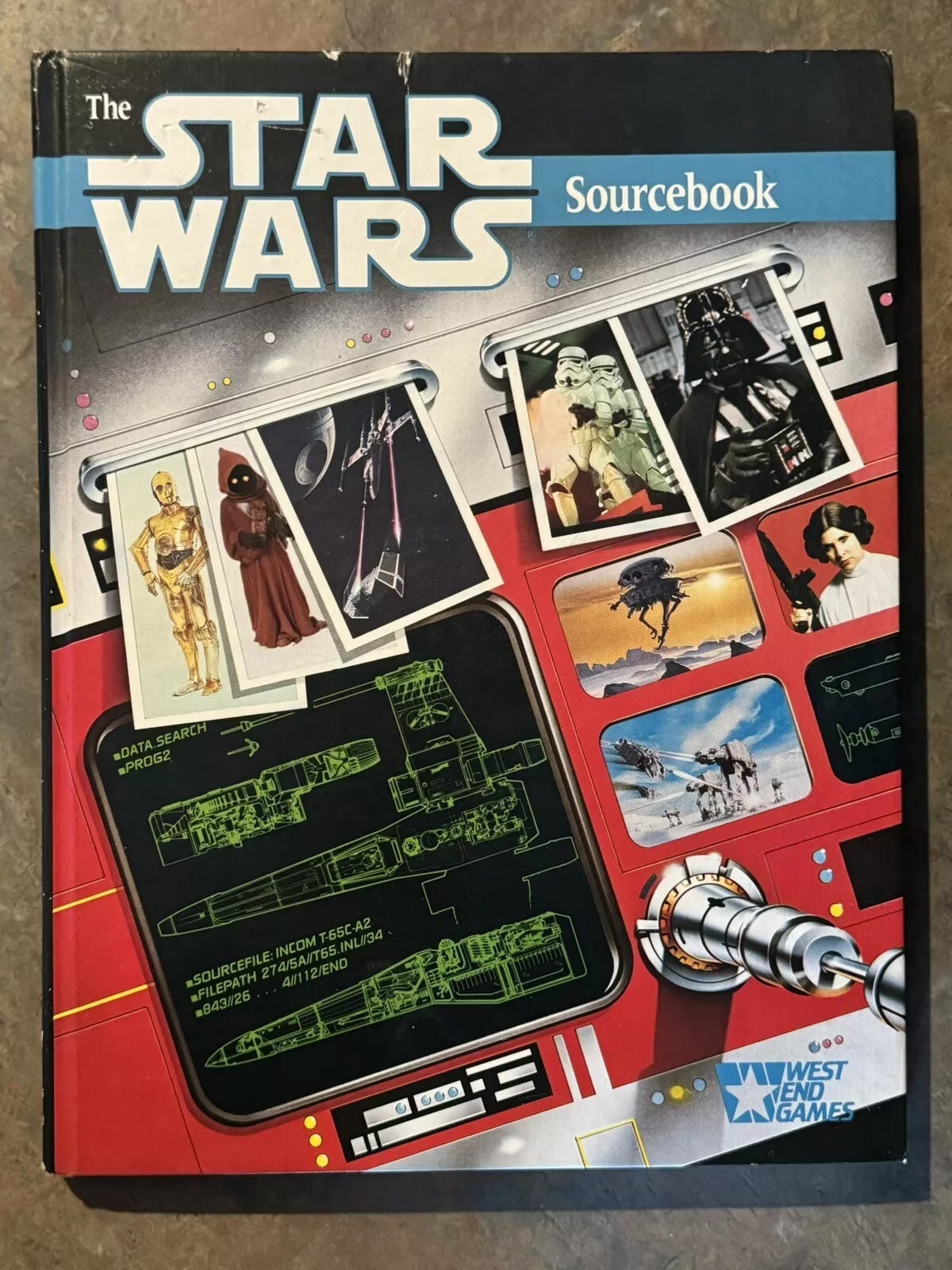

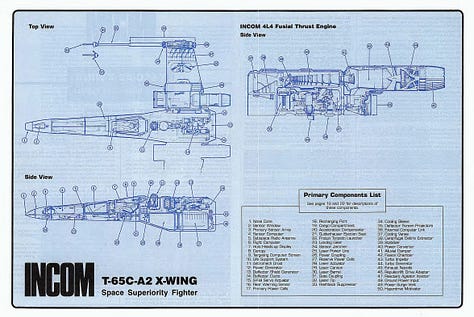

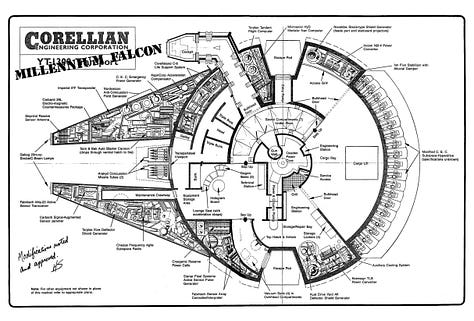

While Costikyan was working on the rule book, Bill Slavicsek, an editor at West End, was overseeing The Star Wars Sourcebook. It would flesh out the details of the universe — everything from how repulsorlift engines and lightsabers and sublight drives worked to the biographical details of characters and the biological makeup of the various monsters and alien races.

Slavicsek was also a huge fan of the film franchise. He had watched them 38 times in the theater. “It so enthralled me that I wanted to go again and again and watch the reaction of my friends and family members to it,” he says. “It was unlike anything I’d seen before. It wasn’t a clean, sterile sci-fi universe — it was lived-in and visceral.”

Slavicsek says that, to his mind, there are fundamental similarities between the universe that George Lucas created and the ones that RPG designers create. “Star Wars and D&D aren’t just telling stories — they’re opening up the imagination,” he says.

Slavicsek started by learning everything he could about the universe of the films. “The Internet didn’t exist back then,” he says. “We had to do all the research ourselves.” He hounded Lucasfilm for photos, magazines, and archival material.

But there were huge holes in the canon that Slavicsek and his co-writer Curtis Smith would have to fill in. Movies simply don’t require the sort of exhaustive world building that an RPG does. The West End designers had to create all that, getting signoff from Lucasfilm on major additions. “We didn’t want to add anything that didn’t fit the milieu, like any tech that seemed too Star Trek,” says Slavicsek.

“Lucasfilm was fairly hands-off,” says Costikyan. “They would have the occasional directive, like, 'you can’t show a stormtrooper with their helmets off,’ I guess because they thought that a property based on the Clone Wars was going to come out eventually. They didn’t want us to kill off the main characters, but we didn’t want to kill them off anyway. We thought players would want to create their own characters in this world.”

Slavicsek was like Adam in the Garden of Eden, giving names to all of the creatures in God’s creation. For instance, there’s a bizarre alien that’s glimpsed briefly in the famous cantina scene from Star Wars that has a long curving neck and eyes on either side of its wide, flat skull. The Kenner toy line simply referred to the creature as Hammerhead. “I convinced Lucasfilm that ‘The Hammerheads’ wasn’t a good name for a species,” he says. “If anything, they’d take that name as an insult.”

Slavicsek renamed the cephalically overendowed creatures Ithorians, and the sourcebook described the herd-like society they had developed on their lushly forested homeworld. He also named the Twi’leks, a race who have two long protuberances extending from the back of their skulls, like the dancing slave girl that Jabba feeds to a giant monster in Return of the Jedi. “Those names didn’t exist until I put them on paper,” says Slaviscek.“It’s neat to see things I invented decades ago show up now in toys and cartoons and novels.”

The sourcebook was studded with artifacts and written as if they were excerpts from actual works from within the Star Wars universe. “We put it together in such a way that statistics were just a small part of it,” says Slavicsek. The book didn’t just describe the characteristics of the giant space slugs that almost devoured the Millennium Falcon in The Empire Strikes Back, it presented a Melville-esque snippet from the autobiography of a spacefarer who had witnessed one ship captain’s destructive obsession with hunting down one such space slug.

![TITLE: The Slug Named Grendel BODY: Call me Sosakar. It was back in the time of the Old Republic, back when the Senate ruled, that I first met Grendel. Aye, the great slug Grendel which, the legends say, awaits unwary spacefarers. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Know you the story of Flandon Sweeg and the starship Darkfire? Know you not? Then listen, and I shall tell. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Flandon Sweeg was a dangerous man, a spacer who, like many others, sometimes resorted to dishonest ways of keeping body and soul together. In the year I re-count, he had come to the end of his tether, and repo agents were hot on his tail. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] His crew bore him no great love, for Flandon was a captain who ruled by force and not by affection. So when he told them how he planned to recoup his for-tune, they abandoned him, every one. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] And this was his plan: a space slug is worth a thousand credits a kilo — to the right corporation. And the space slug Grendel - why, it must have been a million kilos if it was a gram. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Grendel lives in the Borkeen Belt. No one enters Borkeen, that strip of shattered space debris; no one, for no one ever returned - save me. TITLE: The Slug Named Grendel BODY: Call me Sosakar. It was back in the time of the Old Republic, back when the Senate ruled, that I first met Grendel. Aye, the great slug Grendel which, the legends say, awaits unwary spacefarers. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Know you the story of Flandon Sweeg and the starship Darkfire? Know you not? Then listen, and I shall tell. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Flandon Sweeg was a dangerous man, a spacer who, like many others, sometimes resorted to dishonest ways of keeping body and soul together. In the year I re-count, he had come to the end of his tether, and repo agents were hot on his tail. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] His crew bore him no great love, for Flandon was a captain who ruled by force and not by affection. So when he told them how he planned to recoup his for-tune, they abandoned him, every one. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] And this was his plan: a space slug is worth a thousand credits a kilo — to the right corporation. And the space slug Grendel - why, it must have been a million kilos if it was a gram. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Grendel lives in the Borkeen Belt. No one enters Borkeen, that strip of shattered space debris; no one, for no one ever returned - save me.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F92a7c16b-2b15-426d-b424-d7a5b9342ab8_586x636.heic)

There was a narrative richness to the sourcebook that fired the imaginations of players. It didn’t just give the backstory on Han Solo, and explain why Jabba the Hutt put a price on his head, it presented a memo from Jabba’s accountant that itemized Solo’s debts and explained why the Hutt was well within his rights to demand the smuggler’s head. “As always, the decisions of the mighty Jabba are fair, just, and extremely profittable!” writes Fen. (I assume that the double-Ts in “profittable” are a riff on the double-Ts in Hutt and not a misprint.)

![TEXT OF MEMO: Honored Jabba, I have included a list of what this unscrupulous smuggler has cost you, to date, through his unscrupulous actions. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] The amounts listed below are directly or indirectly the result of Solo's decision to dump his cargo, and his equally terrible behavior since then. With your permission, I would like to immediately list them as unrecoverable business losses. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Although it indeed pains you to destroy someone you have long considered as a son (especially before he has a chance to pay off his debts), as you say, Solo's head will serve as a fine deterrent to any other employees contemplating similar actions. As always, the decisions of Mighty Jabba are fair, just, and extremely profitable. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Your very very obedient servant, Calk Fen [PARAGRAPH BREAK] ITEMIZED ACCOUNTING LIST TITLE:Captain Solo's Debts to Jabba the Hutt ITEMIZED ACCOUNTING LIST BEGINS:• Jettisoned spice cargo: 12,400 credits • Dead employee (Greedo): 4,100 credits • Loss of services (Millennium Falcon): 125,640 credits to date (based on last cycle's performance) • Bounty hunter notices: 320 credits • Boba Fett's expenses: 5,000 credits to date (based on a rate of 500 credits per day) • Additional bounty hunter fees: 2,000 credits to date (based on a rate of 50 credits per day per hunter) • 50% Interest:74,730 credits to date TOTAL: 224,190 credits to date TEXT OF MEMO: Honored Jabba, I have included a list of what this unscrupulous smuggler has cost you, to date, through his unscrupulous actions. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] The amounts listed below are directly or indirectly the result of Solo's decision to dump his cargo, and his equally terrible behavior since then. With your permission, I would like to immediately list them as unrecoverable business losses. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Although it indeed pains you to destroy someone you have long considered as a son (especially before he has a chance to pay off his debts), as you say, Solo's head will serve as a fine deterrent to any other employees contemplating similar actions. As always, the decisions of Mighty Jabba are fair, just, and extremely profitable. [PARAGRAPH BREAK] Your very very obedient servant, Calk Fen [PARAGRAPH BREAK] ITEMIZED ACCOUNTING LIST TITLE:Captain Solo's Debts to Jabba the Hutt ITEMIZED ACCOUNTING LIST BEGINS:• Jettisoned spice cargo: 12,400 credits • Dead employee (Greedo): 4,100 credits • Loss of services (Millennium Falcon): 125,640 credits to date (based on last cycle's performance) • Bounty hunter notices: 320 credits • Boba Fett's expenses: 5,000 credits to date (based on a rate of 500 credits per day) • Additional bounty hunter fees: 2,000 credits to date (based on a rate of 50 credits per day per hunter) • 50% Interest:74,730 credits to date TOTAL: 224,190 credits to date](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe6a9720d-b8e9-4e47-a16a-8516d0d4bc9f_774x1032.heic)

When the rulebook and sourcebook launched in late 1987, their popularity caught Lucasfilm by surprise. “I think it began to dawn on them that there was a lot more to what they had with this franchise than they’d thought,” says Slavicsek. “What we were doing gave impetus to other licensees.”

Within a few years of the launch of Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game, Lucasfilm signed off on a new line of Star Wars comics, and Heir to the Empire, a novel written by Timothy Zahn that would explain what happened immediately after the events in Return of the Jedi. Zahn was actually given the RPG sourcebook material to use as a reference when he wrote his novel. “The way I heard it, Zahn was insulted by this at first,” says Slavicsek. “But then he figured that it was better to use our material as a resource rather than have to create a bunch of stuff from scratch.”

Slavicsek would oversee the Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game for several more years, and would eventually be tapped to write several editions of the exhaustive Guide to the Star Wars Universe, becoming one of the foremost authorities on the subject. He continued to design tabletop RPGs, eventually rising to a leadership role at Wizards of the Coast, the company that bought D&D's publisher TSR back in 1997. While there, Slavicsek directed the creation of the third and fourth editions of D&D, and he also co-designed another Star Wars RPG during nearly two decades working at Wizards of the Coast, the role-playing behemoth that had acquired the granddaddy of the genre, Dungeons & Dragons. He’s now a project narrative director overseeing story elements of the massively multiplayer game The Elder Scrolls Online.

The sourcebooks that Slavicsek spearheaded continue to influence Star Wars, even after the vast Expanded Universe was declared non-canonical in 2014. The Story Group within Lucasfilm, which oversees every new narrative element to make sure that it all fits together, includes Pablo Hidalgo. He grew up loving the West End Games RPGs. and contributed to several of the company’s supplements and guides before he became one of the official keepers of the canon at Lucasfilm.

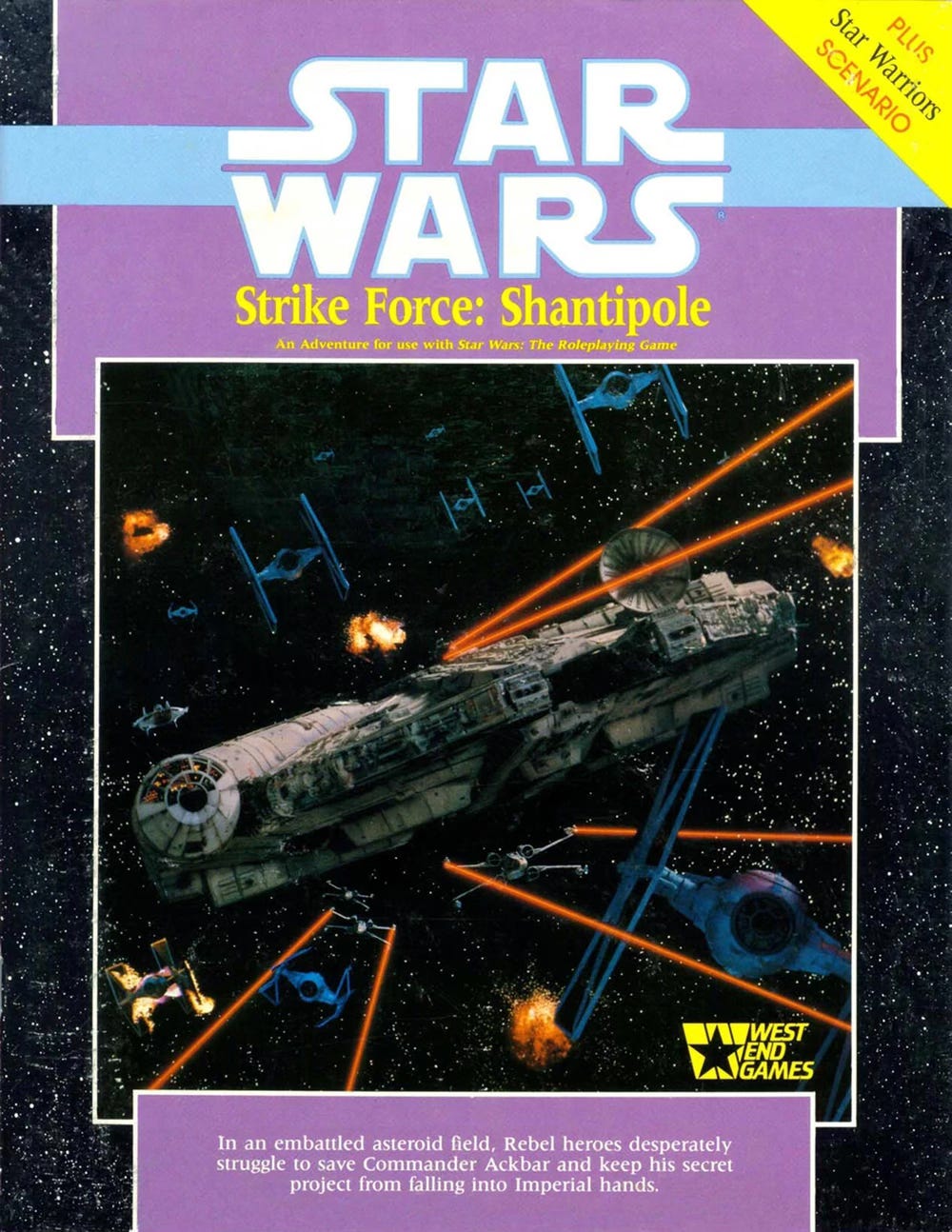

Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game told stories that are still sustaining the franchise to this day. In 2015, Slavicsek saw an episode of the canon-correct TV series Star Wars Rebels that concerned the creation of the B-Wing fighter ship. It lifted names and story elements from “Strike Force: Shantipole,” a 1988 module for the West End RPG that he had edited. “I really get a kick out of stuff like that,” says Slavicsek.

When he was developing the “Rebel Breakout” introductory adventure for the West End Games Star Wars RPG, Slavicsek needed a villain to oppose the players and he didn’t want to simply make it a faceless, nameless Stormtrooper. So he decided that the Empire had elite agents that worked for something called the Imperial Security Bureau, or ISB. Later, he oversaw the making of an entire book about the inner workings of the Empire, The Imperial Sourcebook. It hints at the rivalries and friction within these organizations in ways that definitely seem to prefigure Andor.

“Other than overall tone and direction, Andor has been telling a unique story,” says Slavicsek. “But it’s obvious that someone working on the series is familiar with the West End Games material.”

UPDATE: After he saw this post, Lucasfilm’s official Star Wars Lore Advisor Pablo Hidalgo confirmed that he is one of the people who is putting bits of the tabletop RPG’s story contributions into Andor and other new properties. “The WEG game hit me at the perfect age and let me make my own Star Wars universe,” he posts. “Always happy to bring some of that material forward when I can.”

Hidalgo added, “The original RPG had to, by necessity, fill out what the experience of living day to day life in the fictional universe entailed, a level of granularity never required by the movies. But all that work benefited the steaming future. Episodic Star Wars shows needed to answer such questions as what does money look like? What do people eat? What government agencies affect peoples’ lives? And thankfully these answers were already workshopped in tabletop RPG supplements.”

READ MORE: If you want to go all the way to the bottom of this particular rabbit hole, Bill Slaviscek himself wrote a book called Defining a Galaxy: 30 Years in a Galaxy Far, Far Away in 2018. It details his experience working on the West End Games Star Wars RPG.

"Imagine living in a time when it seemed like the Star Wars phenomenon had run its course." This really brought back memories. When I went to college in the early 90s, Star Wars showings felt downright retro, and nobody could have imagined it coming back to life (and death, and life again) like it did in the decades to come. That's why, I think, the Star Wars "Dark Forces" video game of 1995 felt like an actual moment when it came out. They'd probably do well to hibernate the series again...

Andor is definitely Star Wars “for adults.” Itʻs nice to know that all those richly drawn background details and complex, deep, and morally grey characters had their roots in a tabletop RPG. See? None of us were wasting our time in colleg—er, I mean, high school!