The 45th Anniversary of Gaming's First "Easter Egg"

The console game Adventure popularized the practice of burying hidden features in media

At some point in early 1980, a pivotal game cartridge was released for the Atari 2600 game console. The exact date is lost to history, but I am choosing to celebrate its anniversary this month because the game was the one that established the term “Easter Egg” to describe a feature hidden in the code by the developer. The game is Adventure and its creator is Warren Robinett. I had a chance to interview him a while back about the game and its influential secret. Here’s an updated version of that piece.

Okay, so there’s this yellow guy who lives in a yellow castle, and he's on a quest for a gleaming chalice. He's a total square, and no one could argue that he's drawn with nuance or complexity. But his adventures represent a milestone in video games. The yellow guy navigates complex mazes, hunting for objects that appear in random locations. He does battle with three dragons, each with a distinctive personality. He tracks down keys that are required to unlock impassable gates, all while dodging a thieving bat that's itching to pilfer from him. The yellow guy can even uncover a secret room that contains a secret message that was hidden there by The Creator himself.

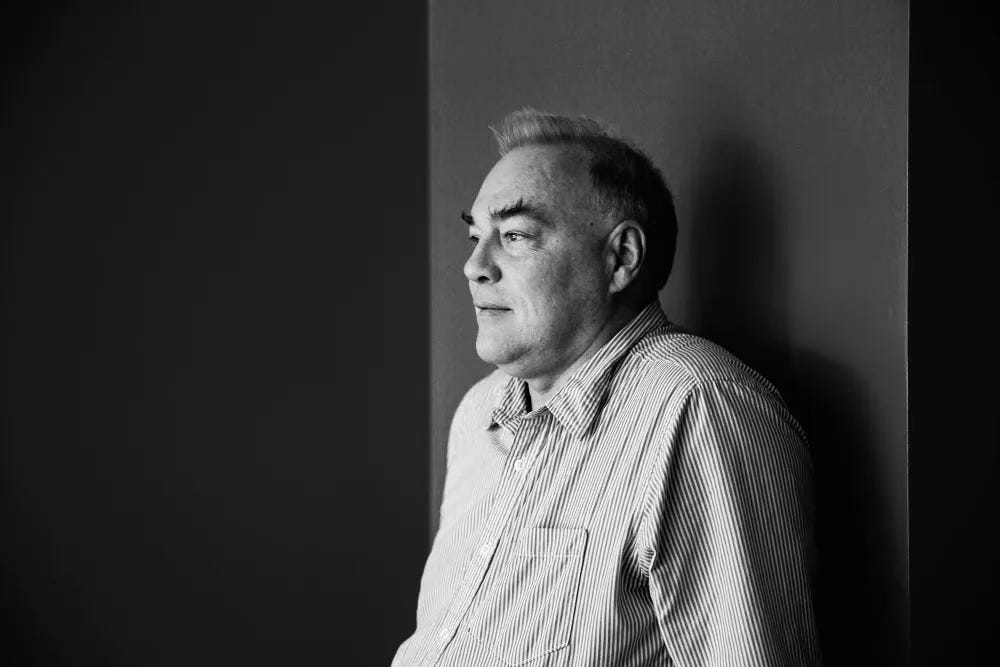

I am of course describing the epochal game Adventure that Warren Robinett created in 1979 for the Atari 2600 console. Robinett was 26 when he programmed the game, entirely by himself, on a 6502 microprocessor. It looks low-res and dated now, but Adventure was among the most ambitious and complex games of its day.

It was also incredibly influential. Robinett essentially created the console adventure game and pioneered several video game tropes that are now so common that we take them for granted. He’s like the early movie makers who hit upon techniques like the close-up and the cut that went on to become the fundamental grammar of film language.

Adventure was made in the era of Space Invaders, when a game’s entire world existed within the confines of a single screen. Robinett came up with the idea that a game could take place on a series of screens, each representing a discrete location. If you steered your avatar off the left side of the screen, it would reappear in the next room on the right side of the screen. “I didn’t set out to make the videogame world bigger than a screen, but I had to,” he tells me.

He set himself the challenge of designing a game that seemed to go far beyond what the hardware of the era was capable of doing, and he took great satisfaction in solving that challenge. He was so proud of it that he found a way to illicitly sign his name on the game, at a time when commercially released Atari titles did not credit the creator in any way. (But more on that later.)

Robinett explained how he made Adventure in a session at the Game Developers Conference in 2015. The game, he says, was inspired by a visit to Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab, where he spent several hours on a mainframe playing a game called Colossal Cave Adventure by Willie Crowther and Don Woods. It was a pure text experience (“YOU ARE STANDING AT THE END OF A ROAD BEFORE A SMALL BRICK BUILDING.”) built around exploration and inventory management. Robinett resolved to adapt that game that had been designed to run on a mainframe computer into something that could be played on the first hit game console.

Making It Seemed Impossible

That seemed impossible on its face. The Atari 2600 was built with graphics-intensive arcade-style games like Missile Command and Asteroids in mind. The standard controller was a directional joystick with a single button, not a keyboard. “Also, Colossal Cave required hundreds of kilobytes of ROM,” Robinett says. The Atari 2600 had 4 kilobytes—about 2% as much. He would have to vastly condense and simplify the game to fit within that limited storage capacity.

The first step was translating the game from a pure text experience to a purely graphical one. Robinett cleverly distilled environments, characters, and objects down to simple, instantly recognizable icons. Except for the deadly enemies—Grundle the green dragon, Rhindle the red dragon, and Yorgle the yellow dragon.

It must be said that these dragons do not look like the ones on the cover of fantasy novels—they look more like giant waterfowl. But using only three different poses, he was able to create two-dimensional creatures that looked vaguely menacing as they roamed the game world, opened their mouths wide to devour you, and crumpled pitiably when you managed to run them through with your sword. “I've become attached to my Duck Dragons,” Robinett says. “If I ever do a sequel, it will be Return of the Duck Dragons.”

Robinett built subroutines into the characters that gave them distinctive behaviors. The subroutines continued even when characters were offscreen in one of the 30 different rooms. [Thirty different rooms! It boggled the minds of kids who got the game in 1980.] The offscreen action made the game world feel even more like a real place and all sorts of emergent situations arose from these subroutines. For instance, you could be devoured by a dragon and trapped in its stomach, only to see that thieving bat fly in, pick up that dragon, and flit around the game world with the two of you in tow. “That wasn’t intentional,” says Robinett. “It resulted from the fact that it was a true simulation.”

Beyond grappling with the severe technical constraints of the console, Robinett had to do battle with his bosses at Atari. They initially discouraged him from tackling such an ambitious project, and then when they saw a working prototype, they pressed him to make it into a tie-in for the upcoming Superman movie. He ignored their demands. “Sometimes you have to fight for your ideas,” he says.

Somehow, Robinett crammed the entire game into the constraints of an Atari cartridge. “I even had 15 bytes of RAM left over,” he says. “There was room to have three more dragons if I had chosen to do so, but it seemed to be working pretty well as is. I guess that’s what you’d call game balancing nowadays.”

So he chose to use that tiny bit of leftover space in the cartridge in a way that he did not share with his bosses. The hidden feature that he secretly added to Adventure is the first widely publicized example of what came to be called an Easter Egg. It’s a sort of in-joke between the Adventure’s creator and players, one that the publisher was completely ignorant of.

The Story of the First Easter Egg

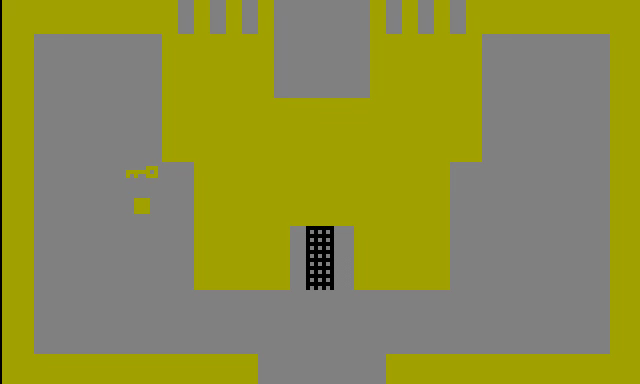

Instead, Robinett used some of that space to build a secret room accessible only through an elaborate series of steps. You needed to find the hidden dot that was buried deep in the catacombs of the Black Castle. The hidden dot is just that—a single pixel so tiny that players only know they’ve found it when they hear the sound that signifies that you have equipped an item.

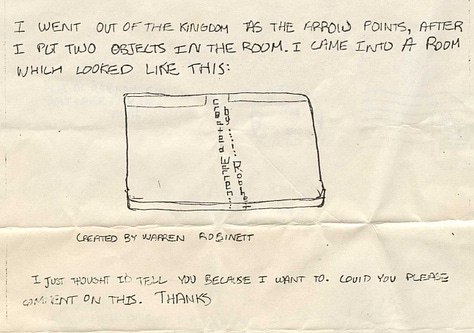

Holding this invisible dot allows you to pass through an otherwise impenetrable barrier and enter a secret room. The room contained the only piece of text in a game composed only of simply blocky shapes. It read: CREATED BY WARREN ROBINETT.

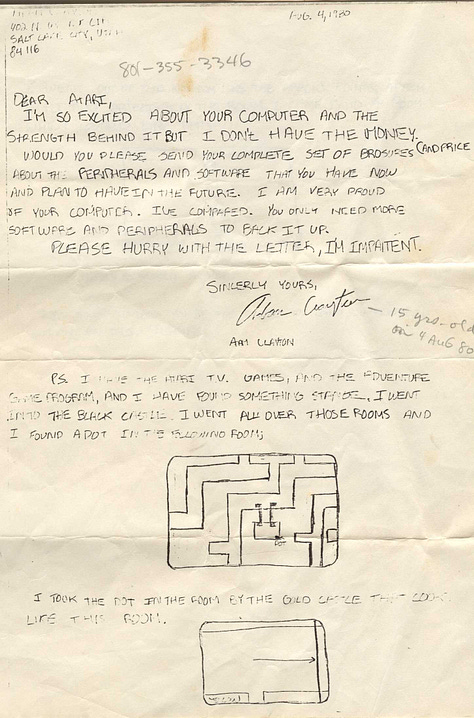

Robinett didn’t tell anyone about it and left Atari soon after finishing Adventure. “I thought of it as a self-promotion maneuver,” Robinett tells me. “Also, I was pissed off. Adventure sold a million units at $25 apiece. [That’s about a $90M gross in 2025 dollars.] Meanwhile, I got a $22K a year salary, no royalties, and they never even forwarded any fan mail to me.”

He has likened this hidden message to the way a painter signs their canvas. He’s also compared it to the hidden messages on Beatles records, “I remembered, from when I was in high school, the rumors that Paul McCartney was dead, and how people played Beatle records backwards, searching for secret messages.” In 1980, it was unthinkable that fans could engage as deeply with such a simple and primitive-looking video game as they did with a Beatles record, or that they’d dig so deeply into it in search of buried surprises.

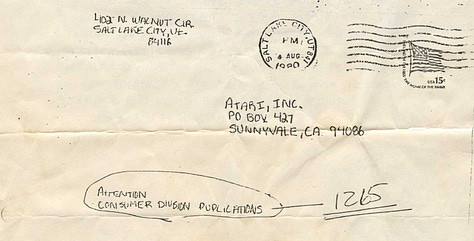

But many Adventure players did, and they found Robinett’s autograph. The first recorded evidence of the discovery of the Easter egg was a letter sent to Atari in August of 1980 by a 15-year-old in Salt Lake City.

The people at Atari were flabbergasted when they received the letter. Until that moment, no one realized that this feature was in the hundreds and thousands of game cartridges they had already sold. Rather than go through the costly process of stripping the secret message out of the code, Atari chose to embrace it.

In 1981, when the new magazine Electronic Games reached out to Atari about the “wild stories” going around about a hidden room in Adventure, Steve Wright, the Director of Software Development in the Atari Consumer Division, didn’t just confirm its existence—he suggested that there’d be plenty more where that came from. “From now on, we’re going to plant little ‘Easter Eggs’ like that in the games,” he told the magazine. (Atari is still a going concern, and they now host a short documentary about Robinett and the origin story of Easter Eggs on their official YouTube account.)

The practice spread widely among game developers, and from games to software, DVD menus, and search engines. Easter Eggs are central to the book Ready Player One, and the film adaptation by Steven Spielberg culminates with the protagonist finding the hidden dot in Adventure.

The Legacy of the Father of the Easter Egg

Robinett’s appearance at the Game Developers Conference was karmic payback for all the fan mail he missed out on. His presentation to a packed auditorium was met with thunderous applause, and he was mobbed by fans afterward. A Google engineer peppered him with intricate questions about his code and his data structure, pulling up a video on his laptop to demonstrate a specific flicker effect he wanted to know more about. Robinett patiently explained the tech, pausing occasionally to shake hands and pose for photos. Then he autographed the grateful engineer’s printout of the disassembled code for the Duck Dragon sprite.

A graphics design lead at AMD gushed to Robinett about playing the game as an 8-year-old. He was too young to memorize the different patterns of the mazes in the game, and he described how terrified he was of being trapped by the dragons as he traversed the blocky virtual realm. “Adventure was the first survival horror game,” the fan insists.

A computer engineer and professor from Brazil asked Robinett to autograph his copy of the book 100 Greatest Console Video Games: 1977-1987, in which Adventure is the first entry. He thanked Robinett profusely as he clutched the book to his chest. “Your game is … everything to me,” he said.

It's all a bit surprising to Robinett, who left the game industry in the early 1980s, moved to North Carolina, and has worked in other fields ever since. For decades, he had no idea that anyone was still interested in his groundbreaking lo-res creation.

“I'm so glad it's not forgotten,” he says.

If you want to go even deeper into the early history of game developers burying hidden secrets, you absolutely have check out this piece by the brilliant digital archeologist Kate Willaert. She scrutinizes several examples that predate Adventure and the coining of the term “Easter Egg.” (Many of these developers, like Robinett, were slipping illicit autographs into their work.) Here is the video version of that article:

![We see the hidden room in Atari Adventure (1980) The player avatar [square] is onscreen alongside to columns of text that run from the top to the bottom of the Screen. The first vertical column reads “CREATED WARREN ….” and the second vertical column reads “BY . . . . | . . ROBINETT.” They combine vidually to form the message “CREATED BY | WARREN ROBINETT.” We see the hidden room in Atari Adventure (1980) The player avatar [square] is onscreen alongside to columns of text that run from the top to the bottom of the Screen. The first vertical column reads “CREATED WARREN ….” and the second vertical column reads “BY . . . . | . . ROBINETT.” They combine vidually to form the message “CREATED BY | WARREN ROBINETT.”](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F698af4bd-8449-44be-ac9a-84208e1cc9ac_640x400.heic)

Thank you for writing about the only TRUE Easter Eggs. Those false easter eggs delivered by bunnies are a travesty and abomination used to distract from the glory of TRUE Easter Eggs that only the //Chosen// (no) Gaming Community (yes) //geeks// (no) //nerds// (definitely no) People (perfect!) understand. You have done well.

Tremendous article. I've read a much shorter version of this article, but this was great. Thank you!